Disconnect

The only fear that overwhelmed me since the beginning of our confined life was the fear of being bored.

Of course, having experienced isolation as a child, and being familiar with growing up in an unsafe world, the fear of catching the virus and dying was relative compared to everything else.

At first, my initial reaction to the crisis was to undermine it and mock those who had started panicking. When a week later the government announced the necessity of a full lockdown for an undetermined period, I started packing bags for the entire family. I ended up with three big suitcases, several books for the children and I, our electronic gadgets, toys and a bag full of medicine. This brought back memories of the war, when my mother packed our stuff (a lot less than I did), took my sister and I, and left the house illegally to take us to a safer place across the border.

The same day we arrived at my in-laws’ beautiful house in a region surrounded by forest. We were among the lucky ones who could leave the city for the countryside. The sun, the sound of the birds, the smell of the wilderness made it more difficult to manage the kids’ excitement. They loved to believe that they were about to start a long vacation. We quickly unpacked the bags and realised how much stuff we had brought. We had been in this rush as if something or someone had been chasing us. We bought groceries as though the end of the world neared, and in a way we did feel that it was indeed the end of the civilised world as we knew it. I told the kids to play outside and immediately started reading the news. I soon became obsessed with it. I would look at my phone every five minutes, feeling as though a giant monster was approaching the country. I couldn’t wait to discover its face and all of its features, so that I could myself judge the monstrosity of it.

Through it all, I was more curious than scared. I loved observing the reactions of government officials, from this country I now call mine. I was amazed to discover how a well-developed and strong democracy like France was dealing with the crisis. It was just as interesting to observe the reaction of its citizens. I noticed a slight disconnect between people and their civic culture. Taken by the fear, the usually polite (to some anyway) and respectful French citizen suddenly started to act with animosity towards the other. Constrained to live for a while outside the secure comfort zone was so disturbing for some that civic manners no longer mattered all that much. People cursed and fought in supermarkets, complained about the neighbours without hesitation, quarrelled with their partners too quickly and took slight pleasure in denouncing people that were not fully respecting the confinement. So many clashed with strong opinions, so many distrusted the capacity of the government to manage the situation and turned this crisis into another opportunity to attack and blame the authorities. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram became war fields where people openly and relentlessly fought with each other.

This disturbed order led me to think that we are about to start an interesting social transformation, or perhaps I was just another one of those idealists who suddenly believed that we are all going to disconnect; let our anger out freely, say and do things we would later regret, but that all of it would eventually reconnect us again to something better.

While days felt like minutes and weeks as hours, my curiosity and amazement faded. My fear of boredom came back. I was scared of disconnecting from the busy life I was living and all the people that were part of it. I started texting friends and relatives more often than usual. I took time to write long messages, I sent songs and poems, funny videos, I called and told them how much I would miss them for the time that I won’t be able to see them. And then we imagined how and when could we properly catch up, and the impossibility of foreseeing a date brought slight sorrow into our souls.

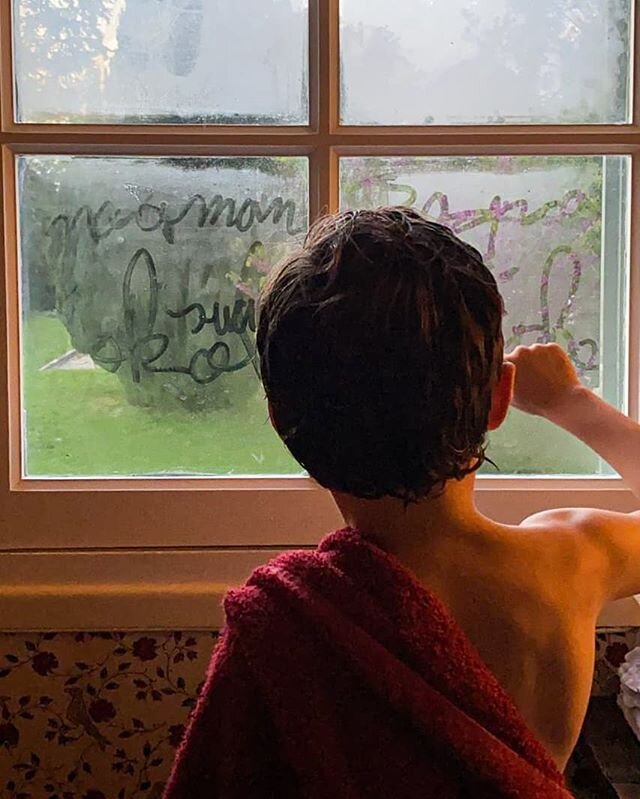

Once I no longer had any news to give or take, no more songs or jokes to share, I decided to accept the state of “boredom”. Very soon beautiful things happened. It felt suddenly good to wake up and have time. Time for self-reflection and deep questioning over my life, my work and my habits. Time that allowed me to reconnect with my truest intuition, without which it is difficult to think freely, to think of possibilities, to make decisions and bring change. I wasn’t alone going through this. A friend surprised me when he expressed his wish of changing life, of moving to the country and perhaps launching a farming activity. Another friend told me she had decided to put words into her entrepreneurial idea that she has unintentionally crushed for years, fearing to even think properly about it. I heard some started writing, others singing or drawing. All these talents emerged freely and brought joy to many of us. And it is in times of joy and happiness, when fully connected with ourselves, that we are capable to love and become better people. It is in times of Covid-19, that we had the time to understand what we had done wrong, how we have neglected ourselves and our loved ones, how much we have missed to simply live.

As the lockdown period matured, the stress, fear and anger slowly exited and the feeling of hope emerged. I would now watch the news with a sense of trust that the situation was being managed, that we would come out of it with more integrity. The young started helping the more fragile by doing their groceries, some companies started delivering goodies for hospital teams, neighbours invited each other for supper and tea, new love stories were born from balcony discussions, and the city enjoyed some time for proper breathing, too.

Not only is this lockdown possibly changing our perception of ourselves and our world in a positive way, but it is also making us better children, parents and partners. If we had forgotten to live together, we have now learned, or at least, we have understood the importance of occasionally disconnecting (from a safe place) in order to connect with ourselves and the ones we love.

Contribution by Tefta Kelmendi. Photo credit: Tefta Kelmendi

The Women of Alexander

It’s come as a chapter, A means to intercept the sentiment.

We happened to meet with the same need to make lemonade. And so we did. Yet the only reason I am savouring this time is because I am running out of it.

People show up when you leave. Everyone wants to make the most of it. And so it’s the feeling of community that probably kills me the most as I leave again. The community of close women friends, Mum and my sister, those who have sat with me through it all. The funny lads of Grey Lynn, our first shared interest in Freida’s and the landlord who became my brother.

Then there’s the questions and honest answers. Are you going to be sad to leave this house? Are you pained to leave your ladies? Of course I have moments of sadness. But I am truly and profoundly happy this chapter of my life is over. That chapter began with our hearts broken to pieces. Thirty-something women finding common shelter. We bonded, we cried. We supported and lifted each other up. We made it to the other side.

There’s what others don’t see, the giant sobs in the bathroom. Tears putting the washing up. The inevitability of detachment and the broken moments. There’s no lack of certainty over the necessity of this change, its roots in what I allowed myself to envision as a life, but the pain of it never lightens. The years go by and the goodbyes get worse. Maybe because movement and distance makes one more intimate with what we may never have again.

The Women of Alexander are moving on. And there is something to be said about the joy and the contentment we also feel. We have done well. We met in sorrow and loss. In bathrooms shared and stories told. They have been my pillars, my partners in crime. We’ve poured our souls over each other and hated each other’s guts at one moment or another. But we made it.

Transitions are tiresome for the body, the mind, the soul. Truth be told, every time I leave a place, it’s a little bit of myself I leave over there. But it’s a version of myself I’m also leaving behind, a phase of my life that is inevitably over.

But it doesn’t have to necessarily be sad. It’s a mix really and in that contradiction, that space in between where you haven’t left but your gutted house isn’t yours anymore, where your mind has started to wonder and you can’t find a damn thing because you’re back to living like a hobo, it’s in that space that resilience kicks in. The growth. The inevitable loneliness of what it is you are doing: giving up a life for the unknown.

Grappling the uncertainty, we learn that surrendering to reality is easier than resisting it at all costs. That no matter what we might think or desire, life sometimes doesn’t go the way we might want. It might’ve decided what could be a better path for you. It’s not because you can’t see it that it’s not there. It’s patience we keep learning here. Tenacity, when facing circumstances beyond our control. When we are tired of wearing the pain. When the in-between has swallowed everything that gives our life a rhythm and some sense of normalcy.

Change is inevitable. What remains is what we make of it. Nobody said we had to be graceful throughout the whole process. Knowing that and accepting the pain I am inflicting on loved ones by leaving them is the uncomfortable I would rather choose. The right thing is to go where I belong for now. And so I will leave you with this: revel in the unknown for it is one of the only places where you will be tested on your ability to cope, where your true character will be revealed and where you will know who your real friends are.

It’s no coincidence we have all had major life shifts happen at the same time. For us and the new house guardians. The Women of Alexander have moved on. We healed. We laugh. Now watch us go and smell the roses.

Contribution by Adeline Guerra. Photo credit: Adeline Guerra.

This month’s MRI theme is “Connection”

Find more work from BrainHug artists on Instagram.

Nationalism and Borders

Not so long ago, some European states came together and committed to creating a democratic union based on post war values. The idea was simple: what if the industries ruling commodities such as coal and steal were pooled together under the authority of a group of European nations, making war between them materially impossible?

The aim was to develop policies contributing to a union that would be politically viable and economically interesting, a place where people would be able to lead decent lives and experience their human rights, effectively contributing to more thriving economies and ultimately stable and peaceful nations that would work together on common problems, rather than repeat the last century.

At the time, most leaders wanted to take concrete action to implement what is one of the core parts of founding documents of the European Union, the free movement of people, goods and services. Soon with the Schengen Convention, the Schengen free zone came to life, abolishing internal border control. Besides reducing costs and serving the economies of its member states, this agreement also served the larger purpose of spreading liberal values.

The idea of a joint European identity was only possible on the condition of respect of freedoms, and most importantly freedom of movement. Successful cultural initiatives such as the Erasmus student exchange program, remain among the few promising projects ensuring Europeans will stick to those values, together. That and over 1 million Erasmus-born European babies since the inception of the program. Go Europe.

Most of the above developments took place within a period of twenty years, somewhere between 1985 and 2000. Looking at it from today’s perspective, these might have been Europe’s healthiest times, and maybe partly explains the fervour with which France has been mourning Jacques Chirac’s death.

During this period, while Europe was turning empty border control points into historical attractions. At the doorstep of the Union, in the Balkans, border crossings were highly dangerous zones. Most of the wartime crimes against civilians in Kosovo were committed at border crossings. Desperate refugees while escaping war and terror unfortunately often ended up in the wolf’s mouth as the saying goes. From humiliation and psychological torture to beatings, rape and executions, borders in the Balkans in the 90s were sources of fear and insecurity.

Yet border crossing was and remains to this day equally a source of hope, and for some populations, an inevitable choice. Be it for violence and war, disasters or very poor economic conditions, people leave countries more often than not because they are pushed to do so. In the early 80s and late 90s European countries and other farther ones opened their doors to migrants and refugees from the Balkans and gave them a chance to rebuild their lives. This approach was coherent with the general position of standing loyal to democratic values, specifically those of humanity and solidarity.

These last few years, things have changed, and maybe this is how I’ll be telling my grandkids the story. War and violent-conflict have become more complex and destructive for humanity, and more difficult to resolve. They are happening in new places, such as cyberspace and while ideology still governs the narrative being presented on all sides, winning people’s hearts and minds has become more preeminent. One element of the narrative has been to call the huge influx of refugees and migrants that has been steadily increasing since 2011 and even before “a global crisis” allowing for the use of language and characterisation of people fleeing violent conflict, slavery, rape, torture and other violations of human rights as not only a threat but also as the rot that would end Europe as we know it. There is no doubt it is a crisis, a crisis of displacement in numbers unprecedented since World War Two (more than 70 million people in the world currently are still displaced from having to flee their homes according to UNHCR) that requires a collective responses to it. Instead, most leaders reacted by closing borders or passing harsh laws on immigration when they are just as responsible as the warring parties for the human suffering that caused people to flee in the first place in their sales of arms and ammunition, their strategic alliances and their lack of consistency in some cases. This is where Angela Merkel will be mostly well remembered by history for resettling 800,000 Syrians in 2015. Let’s not forget though that it was also a sensible economic decision for Germany’s labour market.

But in spite of some sound actions that looked at the issue holistically, the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ has suffered from a vital long-term multilateral approach and has become the scapegoat for the weakening of alliances in Europe and beyond. Growing economic inequality, a rise in the distrust of traditional institutions, coupled with growing unease and feelings of marginalisation for those left behind by globalisation have all contributed to the cultural and political climate we are experiencing today.

The priority has become protection on the basis of national borders, even for countries that once took the lead on open border policy and liberal democracy. Today, some of these countries hide behind the argument that if such protectionist actions are not undertaken, the far right will rise to power.

For all those reasons, we can no longer cross out the possibility of borders coming back to life in Europe. What we believed to be a historical achievement once, the free Schengen zone is fragile and lacks the unified support of its signatories. Countries that voiced out the importance of a value-based democracy, and were main contributors to the maintenance of peaceful and friendly relations are today the ones that raise doubts on alliances and build their electoral systems upon programs of “stricter laws on immigration”, and “strengthening of national borders”.

The discourse on borders has changed because societies are experiencing an ideological crisis. Nationalism is relevant again. While, for the most part in recent history, it was the cause of many battles, its come back proves that after all, societies tend to forget the source of dark times, perhaps because not enough has been done in terms of collective memory. Yet one can easily also question the effectiveness of liberal democracies in creating an equal society with equal opportunity, where people could live according to similar standards and have equal access to health and quality education. The ones that today trust their vote for the return of borders, are the ones that have been precisely struggling and left out from the wealth and comfort offered by globalisation.

Mistakes have been made, and those who will live the consequences the most are the younger generations. They will have to face insecurity, fear and new conflicts. They will need to be innovative in rebuilding a values-based global community and a system that holds it together. They are already learning resistance in ways we haven’t seen in decades, perhaps a silver lining to the Bolsanoros, Trumps and Johnsons of our times. Those of us who have had the luxury of peace have a responsibility to never forget and support collective memory projects that will serve future generations as lessons for what should not happen again and for what societies should be proud of.

Stricter border control, aversion against immigrants and harsher immigration legislation in some countries will only raise anger and create space that keeps nurturing feelings of resentment and hatred towards the other. Such policies can only endanger national security. It is a risky slippery slope towards a divided global society, where countries no longer trust each other and where diversity will become accepted as a threat.

To end this on a personal note, I will always remember the wonderful feeling I experienced when in 2014 I drove through the border between Switzerland and France. There was an abandoned check-point booth at one point, which made me conscious that I was crossing a border. The only other visible difference between the two territories was the colour of the asphalt on the roads. How beautiful, I thought, and I remembered with a smile, that it took me hundreds of border crossings after the war, to start feeling safe and relaxed again. A couple of days following that experience, I came across photographs by Josef Schulz who documented empty border control points in Europe. I thought it was a brilliant project worth sharing for this article.

Contribution by Tefta Kelmendi. Photo credit: Josef Schulz

RELATIONSHIPS

It’s now a common thing to make our relationship status public on social media.

Besides the classical options, there is a third one often easier to choose, and perhaps more comfortable when describing our love situation: “It’s complicated”.

Most of us would agree in describing relationships as challenging, not always worth fighting for. Modern life trends can explain this, but our relationship with ourselves and our personal values and our capacity to love play their part.

Over the past several decades we’ve grown into a society that is to a large extent individualistic. We like making decisions alone, living alone, going to museums alone, traveling alone, walking and running alone, going to nightclubs alone, watching TV series alone, and even going to restaurants alone. A career-oriented ambitious friend living in an expensive European capital, now in his late thirties, explained to me that he has been so happy managing life alone that he can’t imagine making a move that could threaten that comfort. Yet he faces dilemmas sometimes, when he has strong feelings or wants to be with someone and have a family. Another friend wants to be in a relationship but can’t manage. Men she falls for don’t hang in there, for reasons she can’t explain. They rapidly start complaining that commitment is not their thing, even if they love and admire her.

Some people had the idea of facilitating RELATIONSHIPS for our growing individualistic society by developing online dating websites.

Those of us who have tried them know that thanks to them dating and love experiences are being used for business revenue. We’re conditioned to apply with a CV to be accepted into the circle. If so, we pay a monthly fee and only then can we start chatting with at least six people at the same time, go for a drink with a few, enjoy conversations and maybe fall in love with one…but the temptation of going back to the website to find an even better match makes the business grow, and that’s about it. At the end of the three month trial, we still end up coming home alone, watering our plants and going to bed.

And we like this more and more.

We must also reflect on our relationship to our personal values. The degree to which we respect ourselves and what feels right and wrong according to what we value and to what extent we negotiate our values have an impact on our relationship with others. We must connect with our values in every action we take, because that is what will eventually make us happy with who we are, and hence others. This is also probably a prerequisite for identifying how compatible we are with someone. If I value for example privacy, companionship and family, but the other person values solitude, spending time alone, then one can say it’s probably not a perfect match. Yet, when we simply decide to accept the values of the other without needing to negotiate ours, we end up embracing each other’s differences, feeling ultimately loved and accepted.

Finally, love.

Devastated about a previous relationship, feeling lost and unloved, I came across an article explaining the difference between the feeling of love and the action of loving. Suddenly it all made sense. I was still deeply in love, but I could no longer love. It’s necessary to understand that somewhere along the way, things that will affect our ability to act in a loving way may happen. And because of that likelihood, it’s important to stick to healthy communication, gentle words, praising of nice gestures, making them too, being understanding, helpful and happy to sacrifice one’s comfort when the other needs more attention and care. But at times when we struggle at work with a toxic boss, or when we experience a loss in the family, or if we have gained an extra ten kilos and have no idea how to handle a diet, it can be challenging to keep up with the positive loving energy. Frustration takes over and we may as well be envying our partner, incite jealousy, have doubts, and so on. Such feelings that eventually translate into judgmental talk, blaming and shaming, the inability to make joint decisions, fights about authority and ownership, all of which make a relationship toxic and unwanted.

Awareness about all the factors that affect our approach to relationships is necessary for any possible change in how we wish to experience them. We can decide to live alone and try dating sites occasionally, or we can decide to attend more social events and leave space for new encounters and experiences. We are also capable as adults of identifying the necessity to address some personal issues that affect how much we love and value ourselves. Once we take good care of ourselves, there is no doubt we will act in a loving way towards the other. And finally, we shouldn’t be afraid to love and let ourselves fall for someone. Only when we are submerged with loving emotions and act upon them will we reach ultimate happiness both individually and together. The more we love and act in a loving way, the closer we are to experiencing peace, everywhere.

Contribution by Teffta Kelmendi - @Tefta.

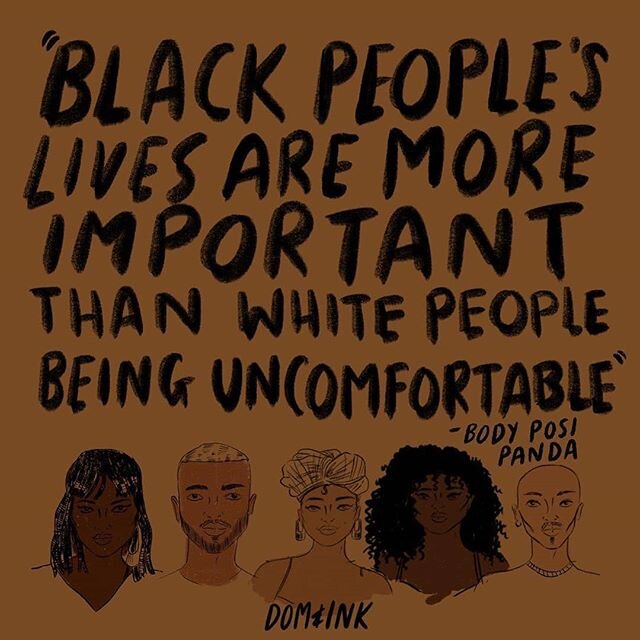

FREE SPEECH

Illustration by Benjamin Leon (@benjaminjleon on Instagram)

Our Truth

I’m a lover of learning. Aren’t we all? Inevitably born as a social being, learning through my environments and learning within my communities. Vygotsky’s certainly got a lot of street cred in terms of emphasising the significance my surroundings have had on my personal development.

Notions of beauty, education, politics, and religion are inescapably connected to the context in which I was born. It’s fair to suppose that much of my culture, values, attitudes and belief systems were in fact learnt.

But what is my truth? And what is your truth?

Never before have our worlds been more connected, our communities more diverse or differing. This is a great thing… right?

In my experience, having been not only exposed but receptive to others’ ideas, perspectives and ideologies have surely prompted new learning. Encouraging diversity and difference sparked curiosity and a yearning for further knowledge and understanding. Appreciating and acknowledging different points of views have given me an insight into my own beliefs and value systems.

We’re all searching for our sense of identity and maybe I’ve found my own truth in others.

Who I am...

What I stand for...

What I believe to be true…

Perhaps our truth is not revealed until our own ideologies and values are questioned; challenged even. And maybe that’s what’s needed?

Free speech and expression of beliefs and insights can and will provoke outrage from within!

But where would we be without outrage? Where would we be without the challengers and the resisters? Examining our own beliefs and ideologies insights deep critical reflection and what’s not to love about a society of critical thinkers?

Maybe we should all take a step back,

chill the hell out, and take a good hard look into our hearts, into ourselves, as we continue to learn our own truth, through other’s truths!

Contribution by Trudi Kareko (@_trudileek)

Home & Belonging

A little joy, that gives me a sense of belonging: The yearning for the sun’s rays as they slowly unravel from behind a spring cloud, a necessity too cold as it is without them still.

Both concepts of home and belonging hold wildly different meanings for all of us.

It’s because I didn’t feel like I belonged that I left the only place I could have called home six years ago. Blaming external factors, I moved from my native Greece to the other side of Europe hoping that this change in my outer surroundings would have an impact on my inner feelings.

In my young ways, I believed that belonging was something I could strive for and achieve.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, moving away did not have the immediate effect I had hoped for. Instead I found myself alone, away from anything I had ever known, having to come to terms with different mentalities, customs, habits and language systems. In my stubbornness and perseverance to fill a need that had no direct or immediate solution, I forced myself into starting over. I became an adult in the process, yet I could not teach myself how to belong.

The existential dread that followed started manifesting itself through anxiety and depressive episodes. Backed by unhealthy coping mechanisms, too readily available as though next to the erasers in the aisle of school supplies or amongst the other cancerous sticks, I faced most days head on.

It was when I had reached my lowest that whoever or whatever chaotically orchestrates existence brought forth support from an unexpected source that I realised that even in its darkest moments life is worth living.

I learnt perhaps the most important lesson so far: that in mindfully recognising the moments that bring me happiness I must always seek out experiences that make life worth living.

The first time I realised I belonged was on an ordinary evening while sitting amongst friends. I glanced at the people around me and was overwhelmingly moved by the realisation that they had chosen in that present moment to be close to me. The atmosphere was filled with mutual admiration as we’d become sources of inspiration for each other’s life and art.

I had belonged way before I had realised it.

It allowed me to be my most authentic self. Still today, it’s when I’m with friends or experiencing the small things in life that I feel the most home.

The word ‘home’ is a common word. It describes our current living situation in everyday conversation; you’re coming home from work, you left your phone at home, when are you going home, and funnily, I’m going home on the 20th, not the house home, “home” home.

We don’t stop to question what it really means to us.

For me, it is not the home that brings the sense of belonging, but the sense of belonging that makes a place my home.

Contribution by Anastasia Baka.

Home & Belonging

In my country, not so long ago, thousands of men, women and boys took arms to fight for their right to exist in their own home.

Too much blood and sorrow was associated with “home” back then – which in this case refers to a small territory in former Yugoslavia where the majority of the people spoke the same language, practiced the same religion, and shared an unfortunate condition together – that of being unwanted because of their ethnic and religious difference. We all know where the aggressive nationalistic agenda of Serbia at that time led to. The world evidenced another Balkan tragedy, where over 800,000 civilians were displaced – most of them expelled forcefully from their homes. About 20,000 women were raped, thousands killed and 1,600 still missing.

This was the reality of the late 1990s, where everything escalated in a matter of weeks - a result of two decades of oppressive and discriminatory actions against ethnic Albanians in Kosovo. At that time, my generation and that of our parents were condemned to a difficult existence, having to resist flagrant violations of human rights, such as the right to education and employment. Childhood memories are marked with imposed feelings of inferiority because of who we were, the language we spoke, and because our parents lost their jobs and were forced to live in misery. Feelings of fear, shame and anxiety where a norm at school - a place where our differences became ever so unbearable. Within one building, classrooms were divided on the basis of ethnicity, and Albanian teachers lacked basic school supplies, were threatened on daily basis and worked without remuneration. The situation worsened over time, leading to a need for resistance and the creation of a parallel education system with schools for Albanian kids taking place in private houses. This resistance was soon going to lose its peaceful nature and transform into an organized armed resistance.

If home is a place of comfort and security, of love and accepting, it wasn’t the home I had!

Yet, it was the place where I was born and raised, where I blew my birthday candles and invited friends for sleepovers, where I first had to defend my ideas and beliefs, the place where I had my first kiss, where I spoke my language and hence I was true to myself and to others. It was the only home I knew and grew to love with an unexplained intensity. It was the place where comfort didn’t come from uninterrupted electricity and hot water, but from feelings of solidarity and belonging.

Today, sitting behind a computer screen in my Parisian flat, comfortably so in a warm apartment where lights never go off on their own, where I can take as many hot showers as I want, a melancholic and slightly guilty feeling overwhelms me. How did I become so familiar with this comfort which was once so foreign ? Only twenty years ago, I was a thirteen year old girl with a backpack following her mother on an uncertain journey. I am lucky that I (still) haven’t found myself in many images that went global of Kosovars crossing borders, or packed in trains while being deported. Today, as a spectator of thousands more images of girls like me who endure the same feelings of fear, loss and humiliation, I am worried of how easily we have instrumentalised disgracing images to appeal for a very human action that (so far) some of us have proved to be incapable of - that of welcoming and helping others in need.

I do not believe that one needs to experience pain in order to grow feelings of compassion. I am convinced that a twenty-five-year-old French boy from Paris with a healthy upbringing, is fully capable of feeling sad when exposed to information and images of people crossing borders, and living in terrible life conditions in camps worldwide or within their own country. He might also feel that he should help and that is a wonderful thing. But what he might have difficulty recognizing – because he has never been deprived of it - is that most of those people dream of going back home, or finding one if their previous home is no longer a safe place.

Twenty years back, finding a home after home for me was a matter of safety and shelter.

But it was followed by the need for belonging, which over the years has become a heavy weight I learned to carry lightly within me.

I find it almost amusing today when I still face situations when I introduce myself and my interlocutor questions where I come from and upon hearing my reply fails to hide their disappointment. And it is absurd when the other in an attempt to express sympathy, goes “Awww, it must have been difficult”, or, “Can you stay in France?”. When I tell them I finished my studies at Sciences Po, they ask “You mean, Sciences Po Paris”?, and with great surprise, they add “BRAVO”. Or, when falling in love becomes a hurtful experience of having to prove what one can't prove through words only - the most beautiful and sincere feeling of love - to reassure the other against fears of a trap for papers. I went as far as talking proudly about my family and showing books published by my father and grandfather to friends and guys I liked, proving that I come from a family of intellectuals in Kosovo, and that we are proud people whose unfortunate fate can never wash away our accomplishments.

Searching for belonging is a journey that requires an open mind and peaceful spirit. It takes courage and pride. For some, it is a choice to build a home where one doesn’t belong, for others it is not. It is also a choice to search for belonging in a place not called home. And finally, it is okay to build a home far from home, and allow ourselves to belong.

At the end of the day, when I finish work feeling tired of switching from one foreign language to another, I come to my comfortable and cozy apartment I call home today, where I live with my children and where we sit daily to do french and albanian homework.

Often, after I put them to sleep and a heavy dark silence fills the living room, I lay back thinking what my life would have been if my mother would have not taken us through that journey twenty years ago.

In a precious hidden place within me, a wish will always remain alive – that of going back to where I will forever belong, and to the only place I can always call home.

Contribution by Tefta Kelmendi.

Giving the Word Refugee its Meaning Back

This past month we published our first Monthly Resonating Images, a promise to 2018, before the year folds into itself.

It’s exciting because it’s our first purely creative collaboration as a global collective. It’s also challenging, because there is a lot to say and few words that can relay a world of experience. We chose this first theme because refuge is how a lot of us met, through working in camps and meeting refugees as aid workers or content producers to having been displaced by war and living with survivor guilt. We’ve all shared deep moments together and we have a lot to say.

We thought we’d start with what’s united us and what we see as a travesty of our times: the instrumentalisation of peoples, the discrimination over those who’ve suffered the most and carry the worst trauma to the vilifying of others and the use of fear as modern-day religion, the darkest sides of human nature creeping up on our times.

Our take is uncensored, collaborative, supportive. The idea behind BrainHug was to create a space for creatives and activists to come together and create what we think is a story worth telling. It originated from a common desire to do things differently and break from the carcan of traditional communications on the issues that hurt, upset or are generally considered hard to grasp.

We want to share the authenticity of the exchanges we experience with those we photograph, paint, film, write about because we believe we can take others there with us. We also dare because we know we can’t please everyone nor do we want to.

We talk of giving the word refugee its meaning back because it has been stripped of all dignity.

It carries a bias, associated with crime, terrorism, the threat of economic downfall, insecurity and the other. From a human needing protection to what is feared most. The person: her struggles, dilemmas and originality absent. Her voice lost in the noise, more often than not conveniently packaged to support charity fundraising efforts. When the end goal remains to get as much aid over, better use what’s always worked than try and tell the real story.

The experience of refuge and the story over what being a refugee means is layered, varied, intimate. Life-changing.

This is what it’s meant for me. Behind the photographs are sweet cups of tea, long hours of driving over to remote places where people were living with nothing, unschooled children, long silences and lots of corrugated iron. Wind. Cold. Overworn pairs of shoes. Plastic chairs and meetings under tents. Mud. NGO logos. Water tanks. Emergency latrines. Incredible hospitality. Delicious coffee. Smiles and benevolence. Despair. Skin diseases for fewer showers. Missing limbs. Trauma. Solitude. Bloody pictures of dead relatives on smartphones. Don’t look away, they are showing you what haunts them the most. Tears. Sick children living in humid garages. My white privileged guilt. Helplessness. Anger.

Connection and love. Lots of love. Laughter when we were setting up the camera, being asked whether their testimony would be featured in “America’s got talent” or “Al Jazeera”, not for lack of pitching. The deep voices of women who’ve seen it all and beyond. The forced resilience, the one that keeps showing up in NGO communications, the flag of all positivity, but look, they’re resilient, what else would you be if you had no choice? The humanity. When all things we won’t miss when we’re dead fail us when we are destitute, all that is left is dignity, character, values, how we treat each other. This is what the word refugee means. It means survival by all means and digging deep into the wells of humanity. Empathy. Humiliation. Safety. Poverty. Shame. An official status card. A moment in time. An endless waiting room. One that strips children of their childhoods and imposes the most painful losses on families. Lack of choice and circumstances. But it isn’t what defines. Nor does it determine.

BrainHug artists and guest contributors, some former or current refugees, others living in countries where refugees are instrumentalised for political means used the blank canvas to say what they think from where they sit. If you feel like it, please share it. For more info about the collective you can find us here.

January’s MRI theme is “Home and Belonging”. If you’d like to submit a contribution, email Manon at Manon@brainhugcreative.com.

Picture: during a meeting with Syrian women in the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon, April 2017

Contribution by Adeline Guerra.